Two facts are indisputable, and they add up to a colossal disadvantage to black Americans. First, people who are officially married are the recipients of massive unearned benefits and protections. Second, far fewer black Americans than white Americans are married.

It does not have to be this way. Marital status does not need to be a ticket to privilege. That unearned privilege does not need to be written into more than 1,000 federal laws. But it is.

Unmarried black Americans fare worse than unmarried white Americans. That shouldn’t happen. They also shouldn’t have to marry to have equal outcomes. No one should. But it turns out that tapping into all those federal perks and protections by getting married does not level the playing field if you are black in the United States. White Americans who are married are doing far better than black Americans who are married in one consequential domain after another. For example, they are less likely to be unemployed, more likely to be homeowners, and they have greater wealth.

The Unearned Benefits and Protections Awarded Only to Married People

The federal benefits available only to people who are legally married include many economic advantages. For example, married people in the U.S. have many more opportunities to tap into Social Security benefits. They have greater access to worker’s compensation benefits, tax breaks on inheritance taxes and estate taxes, and more exemptions from penalties on IRAs. Compared to solo single people, married people filing jointly always pay less in income taxes on the same taxable income.

Legally married people also have special benefits related to health, children, immigration, and much more. (A more comprehensive discussion is here.)

Lisa Arnold and Christina Campbell estimated the lifelong financial cost of being a single woman, using just a subset of known disadvantages — income taxes, Social Security, IRAs, health spending, and housing. They found that married women enjoy a cumulative lifetime advantage of more than a million dollars.

Unearned benefits are not just dished out at the federal level. States and local governments can get in on the act, too. So can companies and workplaces.

Disadvantages that are written into laws and policies are especially consequential because they are structural, systematic, and enforceable. But what I call singlism (the stereotyping, stigmatizing, and marginalizing of single people, and the discrimination against them) also ranges far afield into social, cultural, political, religious, educational, medical, military, personal, and interpersonal realms. (Click here and scroll down to “Further Reading.”)

Far Fewer Black Americans Are Married

According to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau, for 2019, just over half of all people, 15 and older, are married: 53.6%. (I prefer to base my estimates on adults who are 18 and older, but some people do marry when they are younger.) For white Americans, 56.2% are married, and the others are divorced or widowed or have always been single. For black Americans, only 37.5% are married.

The massive unearned advantages accorded to married people in laws and policies, and informally in just about every domain of life, reach fewer than 4 in 10 black Americans.

Black Americans Still Fare Worse than Whites, Even If They Are Married

The marriage fundamentalists would suggest a simple solution: unmarried Black Americans should just get married. They love saying that in any context. But no one should have to marry in order to have equality. Instead, all Americans, married or unmarried, should be treated equally with regard to taxes, Social Security, housing, health care, and everything else.

But how much does marital status really matter? Is it even more disadvantageous to be single in America if you are black? And, does marriage erase any disadvantage? Are Blacks who are married no longer disadvantaged relative to whites in domains such as unemployment, homeownership, or overall wealth?

Unemployment

Back in January 2018, when the economy was still growing, Annie McGrew, Galen Hendricks, and Kate Bahn of the Center for American Progress made the important case that the economy wasn’t so great for people who were single. It was particularly terrible for black Americans who were single, especially the men.

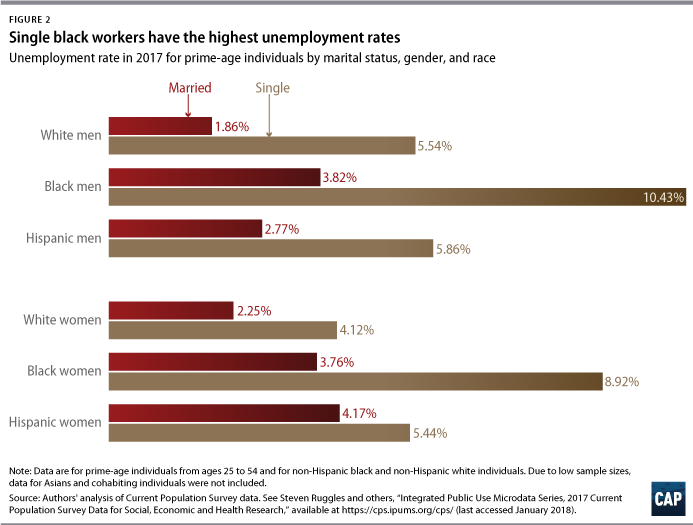

This figure from their article (used with permission) compares the unemployment rates for people who are currently married to those who have always been single and are not cohabiting. (Other categories – divorced, separated, widowed, or cohabiting – were not included.) Hispanics are included in the graph but my focus on this article is on black-white differences.

Single vs Married

The first thing to notice is that single people always have higher unemployment rates than married people. That’s true for black men and women, and white men and women.

Just Looking at Single People: Black vs White

Second, black single people have much higher unemployment rates than white single people. At 10.43%, the unemployment rate for black single men was nearly twice that of white single men, 5.54%. For the women, the unemployment rate for blacks was a little more than twice that of whites, 8.92% vs. 4.12%.

Just Looking at Married People: Black vs White

Third, black Americans who are married still have higher unemployment rates than white Americans who are married. For men, the unemployment rates were 3.82% for the married blacks vs 1.86% for the married whites. For women, the unemployment rates were 3.76% for the married blacks vs 2.25% for the married whites. Marriage did not magically erase racial disparities.

Homeownership

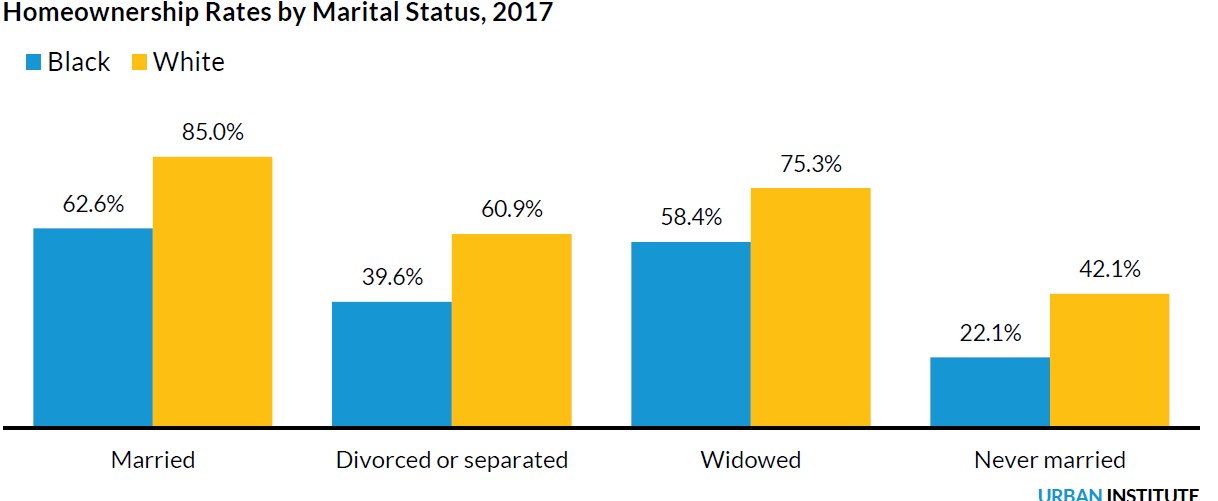

At the Urban Institute, Jung Hyun Choi and her colleagues compared the homeownership rates of blacks and whites of different marital statuses, using data from the 2017 American Community Survey. The graph below is used with their permission.

Single vs Married

Once again, the Americans who had always been single (“never married”) always had lower rates of homeownership than the Americans who were married. For whites, the percentage of homeowners among the currently married people was more than twice that of the single (never married), 85.0% vs 42.1%. For blacks, the percentage of homeownership among the currently married was nearly three times that of the single people, 62.6% vs 22.1%.

Just Looking at Unmarried People: Black vs White

Second, looking just at the unmarried people, blacks always have lower rates of homeownership than whites. For the single (never married) people, the rate of homeownership for whites was almost twice that for blacks, 42.1% vs 22.1%. The difference for the divorced or separated was substantial, too: 60.9% for whites vs 39.6% for blacks. White widowed people also had higher homeownership rates than black widowed people, 75.3% vs 58.4%.

Just Looking at Married People: Black vs White

Third, black Americans who are married still have lower homeownership rates than white Americans who are married, 62.6% vs 85.0%. Again, marriage did not magically erase racial disparities.

Pre-Retirement Wealth

What kind of shape are women in, financially, when they approach retirement? Fenaba Addo and Daniel Lichter examined the total wealth of more than 7,000 black and white women between the ages of 51 and 61. They also assessed the extent to which the women’s marital status and marital histories mattered.

Women in the oldest cohort (born between 1931 and 1941) were interviewed starting in 1992. Women in the youngest group in the study (born between 1948 and 1953) were added to the study in 2004.

Total wealth was a sum of income and asset categories such as checking and savings, stock portfolios, the value of vehicles, and the net dollar value of the primary residence.

Predictably, the married women who were nearing retirement had accumulated more wealth than any of the unmarried women (divorced, separated, widowed, cohabiting, or always single). Averaged across black and white women, the married Americans had about $44,000 more.

The racial differences were even bigger. Averaging across marital statuses, white woman headed into retirement with about $200,000 more in total wealth, compared to black women. The median wealth of black women was only 18% of the wealth of white women.

Of all the factors that comprise total wealth, the one that contributed most to racial disparities in the authors’ analyses were differences in home ownership. If housing wealth is excluded from the measure of total wealth, then pre-retirement black women have only 10% of the wealth of white women, not 18%.

What if black women had the same marital and relationship history as white women? Marital history takes into account not just current marital status but also factors such as previous marriages. Here’s what Professors Addo and Lichter found:

“If Black women had the same marital and relationship histories as White women, then Black–White differences in wealth would be reduced by roughly 10%.”

Once again, even black American women who are married – and even those who have the same marital histories as white women – still end up with far less wealth than white women.

Being married helps. There are lots of unearned financial advantages to marrying. But, as the professors pointed out, other factors matter much more. Employment histories, for example, make a much bigger difference. They account for about 40% of the black—white disparities, compared to the approximate 10% attributable to marriage.

[Notes: (1) The opinions expressed here do not represent the official positions of Unmarried Equality. (2) I’ll post all these blog posts at the UE Facebook page; please join our discussions there. (3) For links to previous columns, click here.]